Today is my favorite day in France. It’s June 21, the longest day of the year and the one day of the year when entire neighborhoods in France turn into a huge block party.

Every year, I celebrate by heading to the 19th and moving from spot to spot, enjoying everything from French rap to classical music, African vibes, and electro.

But why does France celebrate the summer solstice in such a way? To find out we need to go back to Paris in the 1970s.

It was in 1970s that Joel Cohen, an American musician, spent a few years as a producer for radio station France Musique. Originally created in the 1950s as France’s national classical music station, the onset of rock and rock in the ‘60s and ‘70s led to division at the radio station about whether to expand to other musical genres. Which is why in 1975 a change in leadership and direction meant that younger staff were hired and the musical genre expanded.

While the experiment only lasted a few years and the radio station soon returned to classical music for which it is still known today, during that time Cohen proposed a special program called "Saturnales de la Musique" on June 21 and December 21 to celebrate the solstices with live music all night long. At the same time, Maurice Fleuret (a French composer who later became part of the Ministry of Culture) was at the helm of a weekly program on France Musique.

While Cohen’s “Saturnales” didn’t take off at France Musique, it seems that Fleuret liked the idea. After he was appointed the director of music and dance at the Ministry of Culture in the 1980s, he wanted to find a way to bring music and people together, declaring that "the music will be everywhere and the concert nowhere.”

So in 1982, Fleuret, along with Jack Lang, the French Minister of Culture, proposed a day when all musicians across France, both amateur and professional, would play for their neighbors for free. They proposed June 21, the summer solstice. Otherwise known as St John’s Day in France, it’s the shortest night in France, with the sun setting around 10pm.

They decided to call it Fête de la Musique, which means music festival. But when spoken out loud, it sounds similar to faites de la musique, which translates as “make music.” If I’ve learned anything about the French in the last two years of living in Paris, it’s that they love puns and play on words, a lot more than we do in the U.S.

The first Fête de la Musique was not well thought out and neither Fleuret or Lang knew if it would be a success. A few posters were printed and the main players in France’s music scene were told about the event last minute.

In the end, thousands of people turned up. Musicians played on every street corner, garden, and alleyway across France. People turned up in droves, all listening and dancing to music, some of it good, some of it bad, all of it for free.

Although the concept originated as being about French music and musicians, it didn’t stay in France. In 1985, other EU countries adopted the same idea for the European Year of Music. In 2017, the day of music was celebrated by more than 120 countries.

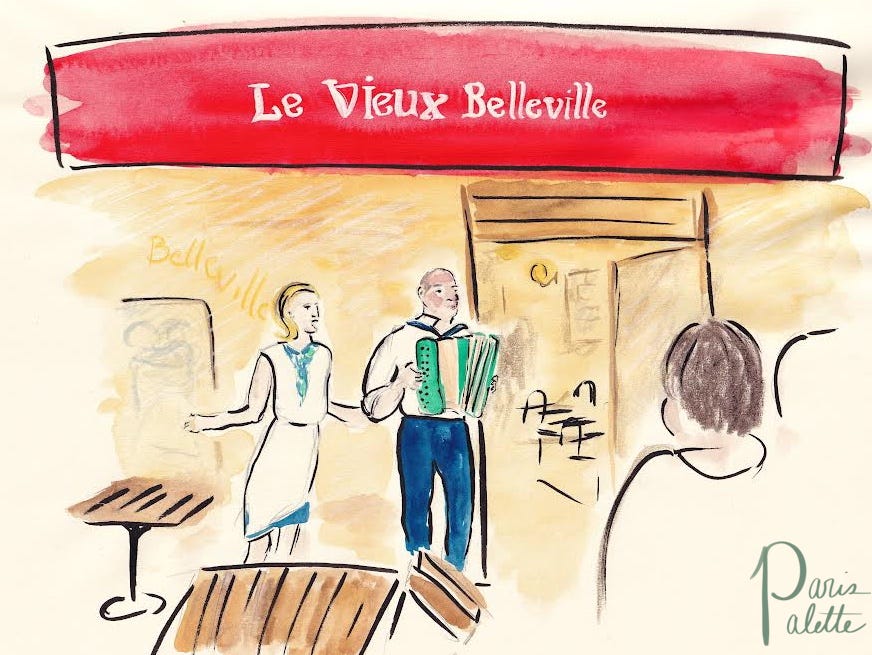

The Fête de la Musique has become a staple of French culture, so much so that they made a stamp for the festival in 1998. Today, there will be concerts from both professionals and amateurs. In Paris, nearly every bar, restaurant, and store will open its doors with musical events, while some musicians will just play randomly on a street corner.

So if you’re in France right now, clear your calendars for a night full of dancing and music.

À la prochaine fois,

-Moriah

Interested in seeing more illustrations from me? Follow me on Instagram

Sounds wonderful! Have fun. Wish I were there. :)